Cultural Appropriation - Part 3: Empire

21 March 2020

- With thanks to Joanna Johnson -

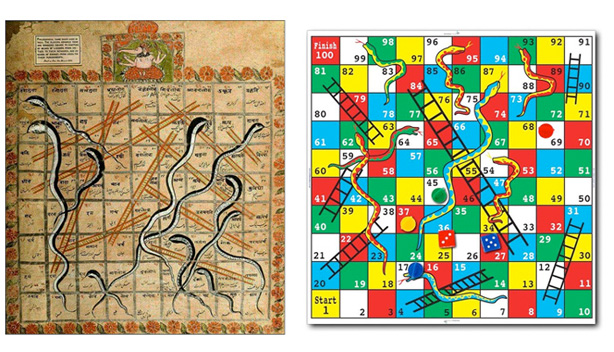

My family was recently given a set of Snakes and Ladders. It’s a cheap, plastic set - a rollup sheet, little pieces (that’ll probably be lost or eaten by the dog) and a dice. As I joined in the game, I was surprised at how much fun it was: my son’s excitement rolling a six and getting an extra throw; climbing a ladder and nearly reaching the top or the disappointment of getting right near the end and then falling back down a snake.

I was fascinated then to learn that snakes and ladders originates from an ancient Indian board game known as Moksha Patam, created by the poet-saint Gyandev in the 13th century. The game’s purpose is to lead its players to a higher plane of existence. The board’s grid represents the journey of life and each square has a positive or negative choice or consequence. Snakes outnumber ladders and are signifiers of various existential obstacles. Ladders are pathways to progress and eventually Vaikuntha - the abode of the Hindu Deity, Vishnu. Moksha Patam is also known as Parama Pada Sopanam and is traditionally played on the night of Vaikuntha Ekadashi - the 11th day after the new moon in the Tamil month of Margazhi. On this night, many Hindus believe that the door to Vaikuntha is opened. Each player is encouraged to identify with their avatar which is represented by a personal effect - like a ring or trinket. Participation in the game serves as a tool for self-reflection and liberation.

Moksha Patam was appropriated by the British in the late 19th century. The game was modified to fit with Christian ideology - divested of Hindu elements and supplanted with Victorian morality. It was renamed Virtue Rewarded or Vice Punished and exported first to Europe and then America in the 1940s under the moniker Chutes and Ladders. Today, Moksha Patam is popularly known throughout the world as Snakes and Ladders - and few people outside of India are aware of its origin and neocolonial displacement.

Yoga was first exported to Europe around the same time as Moksha Patam and there are some striking parallels in the process of its assimilation:

- The stripping away of Hindu ontology

- Installation of European ideals and Christian morality

- The dilution of substance - oversimplification

- Mass production for a global market

Moksha Patam and Snakes & Ladders

The Company

The history of Moksha Patam is an example of the subsumption and commodification of Indian intellectual property - a process facilitated by the socio-economic conditions created by centuries of European colonialism on the subcontinent. The Dutch, French, Portuguese, Danish, Norwegian, and British all exerted colonial power in India at various times. But it was the British in particular who, for over two hundred years, ruthlessly and systematically bled India of its wealth and resources and culture.

British rule was instigated through trade and the brutal regime of the world’s first global corporation - The East India Company (EIC). Chartered by Queen Elizabeth I in 1600, EIC was the first ever “joint-stock company” - and the template for what would become the multinational corporation of today. The crown granted EIC a monopoly on the burgeoning trade to the east and a license to “wage war” where necessary. In the following centuries, EIC viciously exploited the power vacuum created by the collapse of the Mughal empire and from its London headquarters grew into one of the most powerful and violent organisations in the world. The company’s portfolio included spices, silks, tea, slaves, gunpowder and opium. Its modus operandi routinely included plunder, murder, annexation, extortion, and from the latter half of the 18th century, merciless taxation and unelected governance.

EIC recruited Indian soldiers to defend its business interests so that its acquisition of wealth and military power grew exponentially. By the time EIC captured Delhi in 1803 they had amassed a private army of 260,000 soldiers - a force more than twice the size of today’s British Army. The company capitalised on support from within the British Government, many of whose members were themselves shareholders and beneficiaries of the company. EIC was effectively an unregulated multinational corporation with its own private army. Company officials described themselves as ‘the grandest society of merchants in the universe.’’

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, India’s share in the world economy had been 23% - when the British left India in 1948, it had dropped to just over 3%. During this period, the prosperity enjoyed by the British ruling and mercantile classes and the platform for subsequent British global power was paid for by the unimaginable hardship of the citizens of India.

“The Englishman flourishes and acts like a sponge, drawing up riches from the banks of the Ganges and squeezing them down on the banks of the Thames” - John Sullivan - EIC official

It’s impossible to comprehend the scale of the methodical looting and transference of wealth & resources from India to the UK, the cost to millions of families and the legacy of financial hardship and inequality that would last for generations to come.

During the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the company’s own Indian security forces rose up against their oppressors. After a bloody nine-month conflict, EIC officials secured their victory by executing thousands of suspected rebels. Following this horrific episode, the British Crown took full control of the company, nationalising its assets and acquiescing Indian rule to Queen Victoria.

In the grim decades which followed, millions of impoverished Indians died of starvation as vital food stores were exported to Europe, even while famine raged across India. Newly published meteorological data1 shows that the 1943 Bengali famine, which caused the deaths of as many as three million people, was caused not by the failure of monsoon rains but by the continued policy of diverting Indian food stores to support British war assets. The then Prime Minister Winston Churchill, a figure still lionised and venerated by the British Conservative Party, said of the Bengali famine:

“I hate Indians. They are a beastly people with a beastly religion. The famine was their own fault for breeding like rabbits.” - Winston Churchill 1943

The history of British Colonialism is a history of white supremacist patriarchal capitalism, the birth of the multinational corporation and its symbiotic relationship with monarchy and state.

The Gift

A recent, popular catchphrase is that Yoga is ‘India’s gift to the world.’ Although this seemingly benign notion attributes India with agency, it obscures the reality of colonial history and the economy of the yoga industrial complex. It also perpetuates an orientalist stereotype and legitimises the free liberties taken within modern yoga spaces.

“Yoga is an ancestral gift to the human race. That’s why it’s so successful everywhere, that’s why it’s exploding….it doesn’t belong to India, it’s India’s gift to the world. It’s not based on religion. It’s not Hindu, it predates all religions. Yoga is cross cultural…

You know, it’s an ancestral gift that’s under an evolutionary process” - The Evolution of Yoga by Danny Paradise

The idea of ‘evolution’ here rests upon a fundamental (western) assumption about the world - that history is progressively leading the “human race” towards a western orientated goal - and that when ideas come into contact with the west, they automatically improve and evolve2. And yet, as the case of Moksha Patam clearly illustrates, this isn’t the case. It could be argued that rather than being improved upon, yoga’s development has been arrested and permanently disfigured through its contiguity with global capitalism.

The transmission of yoga from east to west doesn’t start from a level playing field. It begins with a dominant predatory culture feeding off the remnants of a culture it has devoured and economically coerced into submission. Clichéd appeals to universalism and evolution like the one in the quote above typically bypass colonialism and minimise or annihilate completely the role of indigenous Hindu culture.

Most popular styles of yoga in the US and Europe originate from the Indian tradition of Haṭha Yoga. Historically, one of the most important religious groups affiliated with Haṭha yoga is the Nāth - an ascetic order of predominantly Śaiva yogis, dating back to at least the 11th century. According to White (2009), Nāth yogis were the sole religious group in South Asia to identify as a ‘yogi order’ and its members used the title ‘yogi’. Nāth yogis shun societal convention and instead seek Mokśa - liberation, through renunciation and unorthodoxy. The Nāth were an incredibly powerful organisation in medieval Northern India - influencing Kings and controlling key pilgrimage and trade routes. Nāth yogis were one of the first major religious groups to organise militarily against the EIC. The British were appalled and threatened by the Nāth in equal measure and saw them as a direct threat to political and economic hegemony.

In the late 18th century, the impossible demands of taxation by the EIC meant that renunciate yogis found it increasingly difficult to subsist on alms from an impoverished, famine-stricken populace. During the Bengali ‘Sannyasi Rebellion’ groups of militant ascetic yogis rose up against company forces in a number of incidents in the province. They were suppressed with uncompromising force by EIC troops whose weaponry and firepower gave the company a clear advantage. EIC officials subsequently used the legal system to criminalise and curtail the lifestyle of ascetic yogis - limiting their freedom of travel and their right to bear arms. This legislation was particularly devastating for the Nāth yogis.

In the 1891 census, Nāth yogis were officially designated ‘disreputable vagrants’. Many yogis had resorted to street performing as well as begging to survive so that the performance of āsana, postures - became associated with social degeneracy and regarded by the British and some sections of Indian society as a vulgar and inferior form of yoga. The religiosity of Bhakti yoga sat more comfortably with the British’s own brand of Victorian Christianity, and its devotees were also less antagonistic towards governance. Whilst the Haṭha practising Nāth yogis were punished by the British, Bhakti groups were actively encouraged.

The Father of Modern Yoga

From as early as the 16th century, Haṭha Yoga had been well established within the literature of orthodox Brahmanism, and was thus practised by householders as well as renunciate yogis. The Brahmin, Sri T. Krishnamacharya (1888 - 1989) is often heralded as the “father”3 of modern yoga. Yet Krishnamacharya was in fact reluctant to teach yoga to westerners. The India in which he grew up and lived his formative years was very much a colonial territory. From the age of ten, Krishnamacharya lived in Mysuru (Mysore4), a city which had long been an important strategic outpost for The East India Company. Resistance in the area had been quashed by EIC through the conquest of the city and the murder of the unmanageable Tipu Sultan of Mysuru, in 1799. They then installed the more pliable Wodeyars on the throne and the family remained politically and financially indebted to the British.

Krishnamacharya's book Yoga Makaranda (1934) makes clear his views on the appropriation of Indian culture and offers an uncannily accurate prophecy:

“Foreigners steal away, either knowingly or unknowingly, many great works and techniques from our land, and then pretend to have discovered them by themselves. Thereafter, they bring these back here and sell them to us, who buy these things using the hard-earned money meant for running our families. If this goes on foreigners may even do the same thing to our Yoga techniques also.” - Sri T. Krishnamacharya

It’s hardly surprising then that four years later, when the actress Eugenie Patterson asked Krishnamacharya to teach her yoga, he refused point-blank. Patterson is perhaps best known by the Hindu stage name she adopted Indra Devi. She was the daughter of a Swiss banker and Russian noblewoman, the wife of a Czech diplomat and a guest of Maharaj Wodeyar. She wouldn’t accept Krishnamacharya’s rebuttal and instead went over his head to her host the Maharaj. Consequently “the Maharaja ordered Krishnamacharya to teach her.” (Goldberg 2017). Krishnamacharya was left with little choice but to acquiesce to his employer and monarch. Devi studied for eight months - initially with one of Krishnamacharya’s students and then with Krishnamacharya himself whose respect and friendship she eventually won. Devi was later responsible for bringing yoga to the Hollywood movie set and dedicated her life to the teaching of yoga.

Although Krishnamacharya is often described as the “inventor”5 of modern āsana-focused yoga, Yoga Makaranda reveals a far greater depth to his teachings and a strong adherence to tradition. Five out of the six chapters are devoted to yoga-kriyās, philosophy, mudrās, vāyus and cakras. Only the final chapter deals with āsana - the aspect of his teaching which is typically focused upon in the west. Much has been made in recent years of the alleged influence of bodybuilding and western physical culture on Krishnamacharya's teachings - yet these claims increasingly fail to bear up to scrutiny6 and also perpetuate a eurocentric narrative in which indigenous culture is surveyed, weighed and measured primarily in relation to the influence of European culture.

Krishnamacharya taught comparatively few western students, didn’t teach outside of India and seems to have had little to no interest in gifting yoga to the west.

Education & Erasure

In British schools, we are taught very little if anything at all about the atrocities committed by the East India Company or the state-sanctioned exploitation of colonial territories. Consequently, many people are unaware of the reality of this comparatively recent period of history.

A poll conducted by YouGov in 2016 found that 43% of British people thought that the British Empire was a good thing, while only 19% thought that it was a bad thing. During a state visit to India in 2013, the then British Prime Minister David Cameron said “I think there is an enormous amount to be proud of in what the British Empire did and was responsible for.”

It doesn’t take much scratching to reveal the unpleasant truth beneath this surface-level pride or to see that the stain of colonialism still runs deeply through the fabric of our privileged society. We may like to think of ourselves as somehow exempt or removed from the heinous past of colonialism, but like as not, we are all connected in some way with the legacy of the British Empire. Very few yoga teacher trainings explore these issues. There is scant knowledge of these events and, if acknowledged at all, they are typically seen as existing in isolation from the “gifting” of yoga to the world.

Cultural appropriation is an extension of colonialism. The source of colonialism is an ethnocentric worldview in which other peoples’ land, resources, wealth, bodies and cultures are presumed to be inferior and/or exotic, available to be possessed, dissected, consumed, remoulded and exploited - with impunity and without question. Elements of this same mindset can often be seen re-enacted in the landscape of globalised yoga in which the symbols, words, language and ideas of the yoga tradition are bought and sold to consumers on the open market.

Like snakes and ladders, modern yoga has in many ways been reduced to the level of a child’s toy: beer yoga, goat yoga, acrobatic yoga - all of these things may be playful and good fun, but they are the cheap gimmicks of a heavily commodified tradition and a pale shadow of the purpose and potential of yoga. The context and meaning of the original cultural elements are being steadily obscured by a mass-produced globalised product. There may come a time, perhaps in some parts of America, it’s already here when the word ‘yoga’ becomes so indelibly associated with western capitalism that, like Moksha Patam, its Indian origin will be lost and forgotten altogether.

The final tragic stage and inevitable outcome of cultural appropriation is the extinction of the source culture altogether. The ubiquity of western universalism and its eradication of diversity results in a kind of homogenous cultural imperialism. In the new world yoga order, anyone can be a yogi. Simply purchasing a p.v.c. mat and practising some āsanas once a week enables one to usurp the identity of a ‘yogi’. In Indian traditions being a yogi has meant a great many things - saints, seers, alchemists, hermits, renouncers, even mercenaries and militant dissidents. Common to all is a way of life, a total commitment to a cause that extends beyond the mundane. Whether the identity of the modern ‘yogi’ as a consumer of postural yoga can coexist with the identity of the indigenous yogi seems unlikely. In the west, the title itself has become diminished, diluted and stripped of any intrinsic value or threat to convention.

Conclusion

It’s been nearly four years since I first began researching and writing about this subject. During that time I’ve become aware of a range of complex issues I hadn’t considered before and which I am still trying to make sense of. I’ve learnt a lot about the yoga industry and also about my own role and tacit complicity in modern yoga’s grand wholesale appropriation of yoga.

I’ve also begun to examine my motives for highlighting these issues and question what I’m hoping to achieve. The last thing the yoga world needs is yet another white, male, would-be saviour - trying to fix yoga: to make it all right and to offer some form of solution and salvation from our collective colonial guilt. I’d like to be able to offer up some warm, fuzzy conclusion… It’s all ok, folks. We’ve fucked up yoga big time and uprooted and distorted it from its culture of origin but now here are a few simple steps we all can take to undo that damage. It’s not that simple. Cultural appropriation is deeply rooted in systemic racism, capitalism, ignorance and a lack of respect for other peoples’ cultures and histories.

Over the past year, cultural appropriation has become a hot topic and even Yoga Journal (whose role in appropriation I discussed in part 2) have begun featuring articles on it. Although it’s encouraging that these issues are now being discussed, I think that we need to be wary of yoga businesses and personalities capitalising on this controversial subject - signalling virtue and making an outward show of decolonisation whilst at the same time seeking to benefit in some way from that process. Capitalism assimilates rebellion by commodifying rebellion and then selling it back: thereby neutralising the threat at the same time as generating more profit.

In a sense, the appropriators are appropriating the conversation on appropriation.

It’s impossible to understand cultural appropriation without examining its colonial roots and facing unpleasant truths about our own privilege and identity as white, western teachers of yoga. This was recently brought home quite vividly: my partner and I have opened a small yoga studio in a former silversmith’s workshop in a local seaside town. When, later on, we did some research on the property we found that it was originally constructed and owned by the former governor of Madras - who having made his fortune in India, on returning to England developed many of the properties in the harbour area of the town. Our town and property are by no means unusual. We all need to recognise the uncomfortable truth that the buildings we practice and teach in, the fashionable sweatshop-made yoga pants we wear, the tea and coffee we drink, the imported p.v.c. yoga mats, even the board games that we give to our children - are all built upon the towering edifice of colonial oppression.

And if we then hope to proceed with any form of integrity - then we must surely learn to change our own behaviour and to engage critically with popular yoga narratives.

I’m not yet sure what true decolonisation looks like, but I don’t think I’ll find it in on decolonisingyoga.com. I’m also fairly sure that it won’t come from the colonisers themselves - how can we dismantle a system which we continue to benefit from? Until the mainstream yoga industry can acknowledge its cultural prejudices and welcome Hindu practitioners into the discussion and allow their voices to be heard, then I don’t think meaningful change will happen. Real decolonisation will mean us giving up our inherited privileges, relinquishing our authority and quietly listening to marginalised indigenous voices of the past and the present.

James

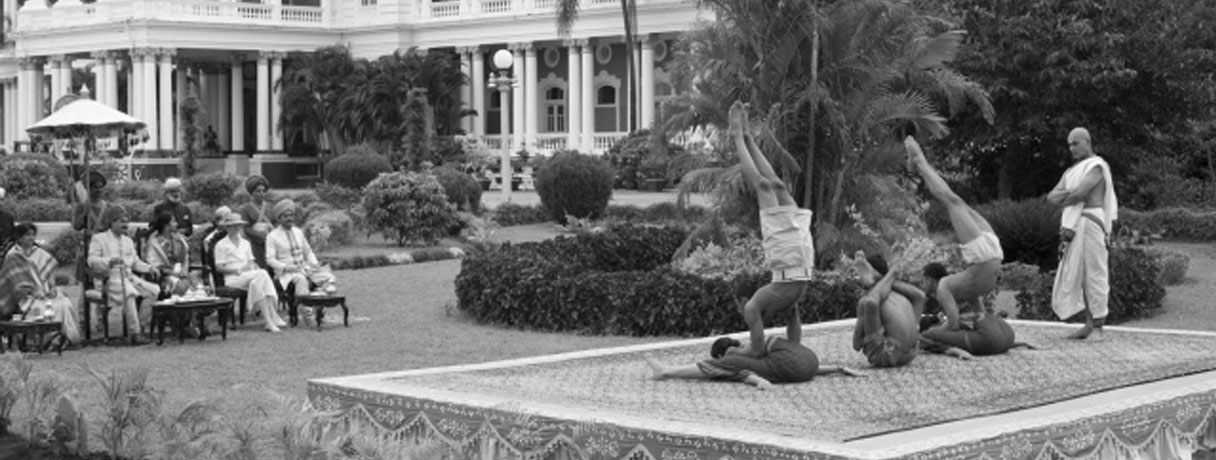

Photo credit:

The title image is from the film: Breath of the Gods, A Journey to the Origins of Modern Yoga.

With kind permission from Jan Schmidt-Garre, director of Breath of the Gods: www.breathofthegods.com

Notes:

1) Michael Safi (2019) Guardian article: Churchill's Policies Contributed to 1943 Bengal Famine.

2) Malholtra (2017) Being Different: Contesting Western Universalism.

3) Wikipedia entry for T Krishnamacharya.

4) In 2014, Mysore changed its name to the Kannada vernacular ‘Mysuru.’

5) Yoga Journal Online May 2017: Krishnamacharya's Legacy: Modern Yoga's Inventor

6) The theory that so-called ‘modern postural yoga’ was largely developed through contact with western physical culture was popularised through Mark Singleton’s Yoga Body in 2010. Since that time, new visual and textual research has shed fresh light on āsana praxis in precolonial India - so that some of Singleton’s historical claims need revision. For more info on new research see references: Seth Powell’s Etched in Stone (2018) and Jason Birch’s The Proliferation of Āsanas in Late-Mediaeval Yoga Texts (2018)

Online References

YouGov: Rhodes must not fall

Michael Safi: Churchill's policies contributed to 1943 Bengal famine - The Guardian

Yoga Journal: Krishnamacharya's Legacy: Modern Yoga's Inventor

Wikipedia: Sri Krishnamacharya

Seth Powell: Etched in Stone… Journal of Yoga Studies

Jason Birch: The Proliferation of Āsana-s in Late-Mediaeval Yoga Texts - Academia.edu

Danny Paradise: The Evolution of Yoga: Youtube

Brown Girl Magazine: How a Popular Decolonizing Yoga Summit Became a Colonizing One

Miyuki Baker: Yoga and Colonization: Lets talk about it

Joanna Johnson: Fuck Your Neoliberal Yoga - Selling Yoga and Selling Ourselves in the Digital Age

Amara Miller: The Sociological Yogi - amaramillerblog.wordpress.com

Rajiv Malhotra: Infinity Foundation - rajivmalholtra.com

Sri Louise: PostYoga, A Manifesto - postyoga.wordpress.com

Geneva Sambor: Lets Talk About Yoga and Colonization

William Dalrymple: The East India Company: The original corporate raiders - the Guardian online

Printed References:

Banerjea, A.K. (1999) Philosophy of Gorakhnath Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi

Chatterji, B. (2005) Anandamath - The Sacred Brotherhood Oxford University Press, New York

Eddo-Lodge, R. (2017) Why I’m no Longer Talking to White People about Race Bloomsbury Press, London

Goldberg, M. (2017) The Goddess Pose Corsair, London

Hooks, B. (1994) Outlaw Culture Routledge, New York

Jain, A.R. (2015) Selling Yoga Oxford University Press, New York

Krishnamacharya, T. 2011(1934) Yoga Makaranda, The Nectar of Yoga English Translation by TKV Desikachar, Media Garuda, Chennai

Malholtra R. (2007) Being Different Harper Collins, India

Mohan, A.G. (2007) Krishnamacharya His Life and Teachings Shambala, Boston & London

Singleton, M. (2010) Yoga Body, The Origins of Modern Posture Practice Oxford University Press, New York

Tharoor, S. (2016) Inglorious Empire - What the British Did to India Penguin Books

White, David. (2011) Sinister Yogis University of Chicago Press, London

Like this article?

Then why not share it with others who may enjoy reading it too:

Buy me a cuppa!

I hope you've enjoyed reading my blog. Perhaps you've learnt something new about yoga or its helped you with your own research and studies. Please help support my work and keep this website running.